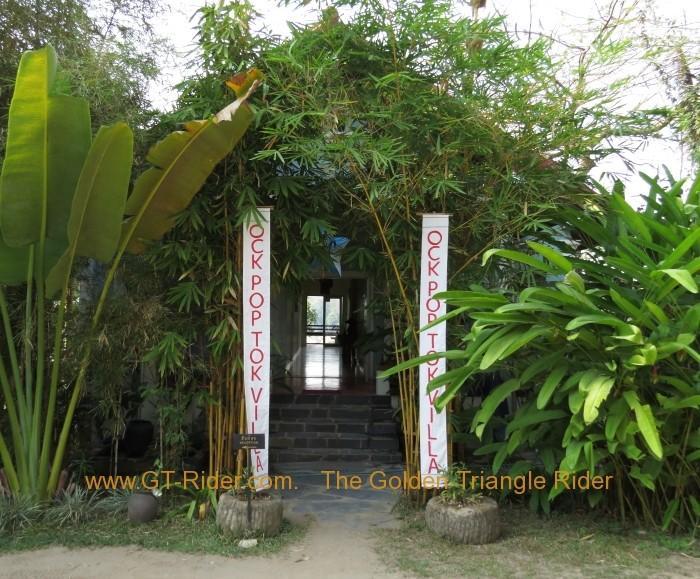

Ock Pop Tok - Lao Weaving Exhibition Centre in Luang Prabang

Ock Pop Tok, meaning east meets west, was started in 2000 by a local weaver and an English photographer. Blending a passion for textiles and a driving force for positive change we are about bringing people together through textiles, exchanging knowledge and ideas to make our world a better place.

The philosophy behind Ock Pop Tok was and continues to be, to empower women through their traditional skills, as well as promoting the beauty of laotian textiles across the globe. Our mission statement following the principles of fairtrade we aim to; advance the artistic, cultural and social development of lao artisans and increase the appreciation of lao’s diverse textiles and communities through educational activities.

This two fold mission statement is achieved through a number of activities and practices. Our ethical trade policy is the basis for our success.

Visit our living crafts centre on the banks of the Mekong in Luang Prabang.......the Ock Pop Tok experience comes alive where east meets west and some say where heaven meets earth....

Learn. In April 2006 Cck Pop Tok founded fibre2fabric a non-profit gallery focusing on handcrafted textiles as a way to explore and explain Lao culture.

LEARN

Create. Take one of our classes and make your own lao textile, bamboo basket or bamboo paper (coming soon).

SHOP

Shop. Our 3 stores present the work of the Ock Pop Tok weavers and village weaver projects. The f2f gallery and our main shop is in the old quarter, there is a lifestyle shop on the main road and the living crafts centre showroom is on the banks of the Mekong 2km out of town.

ACCOMMODATION

Stay. In October 2010 we opened the doors to our villa, a textile design themed residence featuring contemporary Lao design and sustainable living style.

RESTAURANT

Eat. The Silkroad cafe dishes up a blend of the east and the west.

In depth description:

Ock Pop Tok is Laos based social enterprise working primarily in the field of textiles, handicrafts and design. Ock pop tok, meaning east meets west, was started in 2000, by a laotian weaver and an english photographer. Following the principles of fair-trade we aim to: Advance the artistic, cultural and social development of lao artisans and increase the appreciation of lao's diverse textiles and communities through educational activities. The philosophy behind Ock Pop Tok was and continues to be, to empower women through creating opportunities for their traditional skills, and promote laotian textiles across the globe.

In 2005 we opened the living crafts centre, a weaving and dyeing studio, craft school, and exhibition space. Set in a tropical mekong garden it serves as a resource centre for learning about textiles, crafts and culture. On site there is also a café, shop and small guesthouse.

In town, we manage 2 fair trade shops selling the items made from the weaving studio and village weaver projects.

Village weaver projects:

Working in conjunction with the lao national tourism administration, development agencies and the lao women’s union we train artisans from remote areas in refresher natural dyes and weaving skills, product design and business related skills. Craftsmanship and tradition are combined with artistic creativity and market knowledge. Village based production is found to have significant benefits as a whole.

Fibre2fabric:

In April 2006 Ock Pop Tok founded fibre2fabric a non-profit gallery that focuses on handcrafted textiles as a way to explore and explain lao culture. The gallery is dedicated to documenting, exhibiting and upholding the social role and tradition of textiles in the Lao pdr.

So join us and...learn, create, shop, stay & eat.....

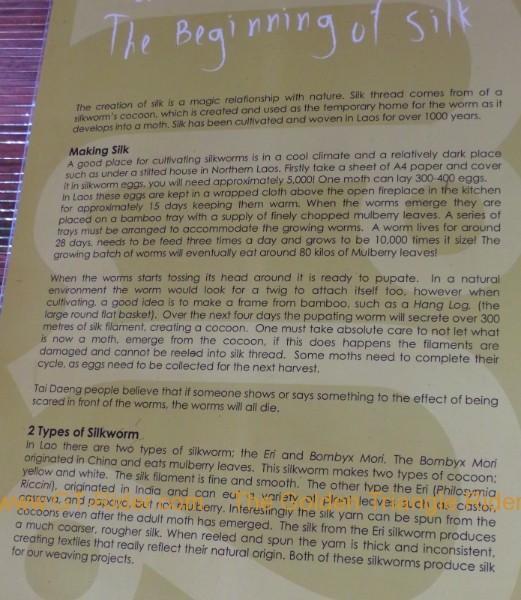

Ock Pop Tok has an excellent weaving display - information

Lao textiles are as diverse as the people here that make them. Laos is a landlocked country with a population of 6.3 million people, the country consists of 49 officially recognised ethnic groups. These groups can be divided like this: Lao-Tai 55%, Khmu 11%, Hmong 8%, other 26% (Katu, Akha, Lanten, Lisu, and other minority groups) (2005 census). Traditionally textiles are made by women, the preparation of dyes and the actual dyeing is done by women and it is women that more often than not still proudly wear the cloths that they make. Materials used in textile creation are home grown; from hmong hemp in the cool mountain air, to silk made from ravenous worms munching mulberry to the organic fields of cotton that produce yarns for soft cloths.If you like textiles then you will love Laos, if you appreciate hand crafted goods then you will have a field day, if you want to see age old traditions and lifestyles then get here quick. Lao textiles are such an important part of lao cultural diversity, but times are changing and its now that we need to secure the place for Lao textiles on the world platform.

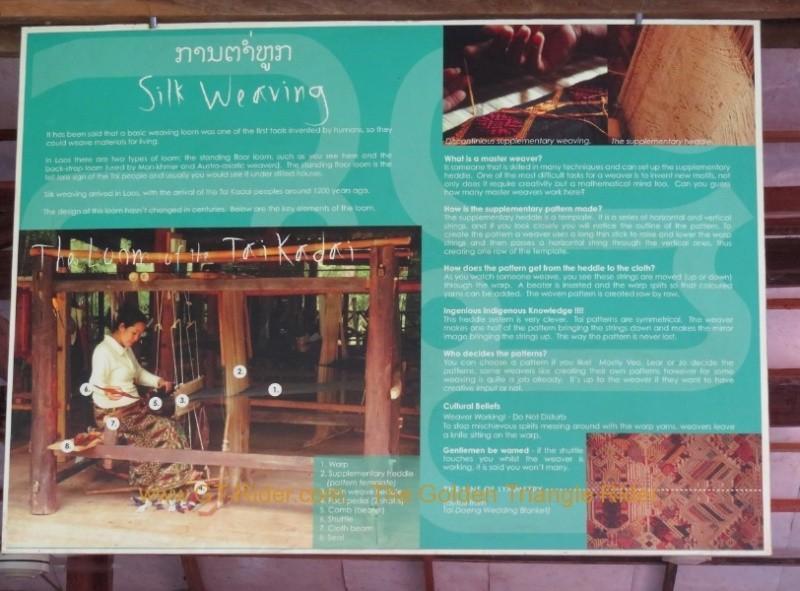

TAI

The Tai can be traced back to the Yunnan area of China, where they were known as Tai-Kadai-Kam-Sui. In 8 A.D due to expanding Chinese dynasties they started migrating southwards into Laos, Vietnam and Thailand. With them they brought the arts of silk making and weaving. Weavers work on floor standing looms, they use a 2 shaft system with a supplementary heddle. The subgroup known as the Tai Daeng excel in the use of this supplementary pattern heddle, weaving intricate weft motifs.

Tai means ‘people of’, so the word following usually states which area they are from. Nowadays one will often hear Lao people refer to themselves as Tai-Vieng for example meaning they are from Vientiane. In Huaphanh Province there are many communities of Tai Daeng and Tai Dam, meaning red and black respectively. Their origins can be traced to the Red and Black Rivers in Yunnan that flow southwards towards Vietnam. Other subgroups include: Tai Phuan, Tai Lue, Tai Moei, Tai Waat, Tai Nuea and Tai Khang.

LAO-TAI

The Lao-Tai are traditionally shamanic people with a strong belief in the afterworld. Nowadays Buddhism is becoming more popular and links to animism or shamanism are looked upon as old-fashioned, thus Buddhist beliefs are increasingly used to interpret icons. Usually textiles depict stories of ancestors' spirits travelling to the afterworld, stories of Nagas and their influences on life around them, Siho – the half lion half elephant figure and motifs inspired by nature and daily life. These motifs appear in various forms of the many different sub ethnic groups of the Lao-Tai and using a number of techniques.

Girls weave items as a dowry, giving her groom’s family the items. Traditionally the woman would move to the man’s family house. A weaver in Muong Vien told us that she wove fabric for 40 floor cushions, 12 matresses, 2 blankets, 2 long pillows, and a curtain to separate the newly weds space in the house. This took her 12 months to complete.

Pha Khan Mon; Girls would also weave small items and give them to boys they sought the attention of. The most common form of love gift was a small handkerchief; in some areas girls wove and made red bags. During the American/Vietnam war, girls wove small pieces and gave them to soldiers for good luck.

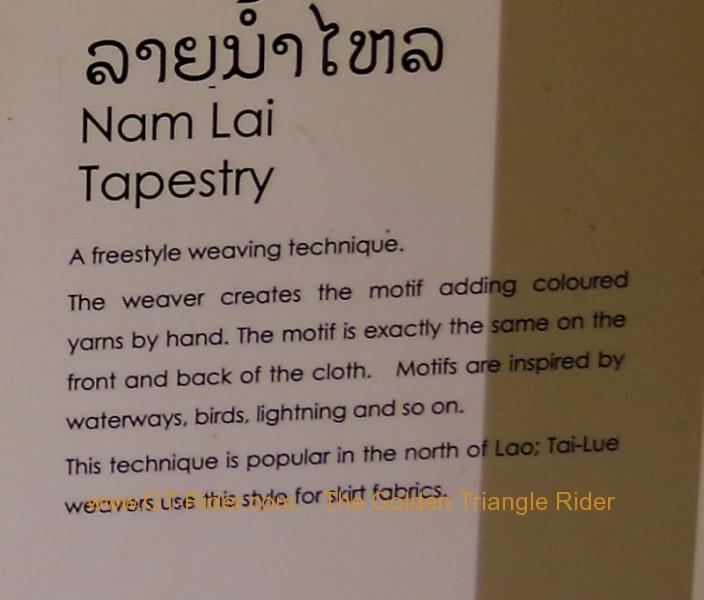

Sihn are still worn on a daily basis. The fabric is tailored with a waistband and darts are added. Lao women are very proud to wear these skirts. The patterns vary according to ethnic group, for example: Tai-Lue wear sihn with horizontal stripes, ikat and tapestry.

HMONG

The Hmong are thought to originate from the plains of Tibet and Mongolia.

Records indicate they started migrating to Lao in the early 19th Century. Their language called Hmong, is classified as a Miao-Yien language in the Sino-Tibetan family of languages, and until recently had no written text. There are a three sub groups; the Hmong Dao ‘White’, Hmong Du ‘Blue’ and Hmong Djua ‘Striped’ distinguishable by their clothing.

Villages are traditionally found high in the mountains. Their one storey houses have low sloping grass roofs. It is common for more than one generation to live together in one house. Hmong are well known for their farming and livestock skills, they practice swidden agriculture, a system that rests the land with a fallow period. Hmong culture is strong, even when they move down to the lowlands their village systems remain intact. There are many Hmong communities around LuangPrabang, Xieng Khouang, Xam Nua and Oudomxai.

Hmong Du and Djua practice indigo resist batik; their skirts are decorated with this fabric. Traditionally Hmong Djua have bands of fabric stitched on the sleeves of jackets. Hmong Dao don’t practice batik, their skirts contain plain white bands of hemp on which they embroider, they are renown for their needle skill.

HEMP FACTS

Hemp comes from the cannabis sativa plant, just one of several different varieties of cannabis. Most people are familiar with the rasta and indica varieties which are known universally as marijuana, derived from the Mexican slang. Both these varieties are high (all puns intended) in THC, the active ingredient needed to get 'high'. Cannabis varieties that contain THC are illegal in Laos and many other countries.

Hemp does not contain THC. It has been cultivated the world over for more than 12,000 years. The latin name for hemp, sativa, means useful. Hemp can be used for many things such as fuel, cloth, paper, food, oil, rope and sail canvas. It is widely regarded as the crop for the future because it has such a low environmental impact. It can be grown and processed without any chemical treatments and yields three times more raw fibre as cotton. Oil made from the seeds can be burned as fuel and has fewer emissions than petroleum.

What is hemp used for?

Daily Clothing - trousers, shirts, jackets, head scarves, hats, protective leggings, belts and shoes.

Household Items - Blankets, bags, string.

Ceremonial Use - Funeral clothing, and new year's clothing: highly decorative jackets, skirts, trousers, sashes and shoes. Strips of fabric as banners in shamanic practices.

VILLAGE WEAVER PROJECTS

Village Weaver Projects are a series of initiatives that create economic opportunities for artisans in rural locations. We help develop ranges of handicrafts that combine craftmanship and tradition with artistic creativity and market knowledge. Our team of weavers, dyers, designers and tailors transfer their skills to aid artisans make a better living from handicrafts. Currently this work takes place in 11 provinces. Combining a passion for these deep-rooted cultures and the handmade traditions with our business saavy we are able to create thriving village enterprises. In most cases we work with a government or NGO partner.

OMA WEAVER PROJECT

Ethnicity: Oma. Language Group: Sino-Tibetan

Province: Phongsaly Project start date: May 2002

The Oma are one of Laos' smallest ethnic groups, with only a few villages in Phongsaly province. Cotton growers, indigo dyers and exquisite embroiderers result in their traditional clothing being both colourful and unique. The remote locations of their villages make trade difficult, but since early 2002 when the Lao Women’s Union invited Ock Pop Tok to support the purchasing of their handicrafts we have maintained a creative and financial input into the production of their handicrafts.

Headscarves and jackets that are still made and worn on a daily basis by the Oma can be found in the gallery. One woman, Amee, travelled to Luang Prabang on a few occasions to work on product designs that she in turn has taught to her fellow compatriots. Have a look for bags and purses that show off their incredible needlework.

LUANG NAMTHA WEAVER PROJECTS

Ethnicity: Khmu, Lanten, Akha. Language Group: Mon-Khmer, Mien-Yao, Sino-Tibetan

Province: Luang Namtha Project start date: 2004

Veo’s brother, Dr. Phouvieng, is a doctor based in Luang Namtha. Working in the field, he realised that there were mutual opportunities for the remote communities and his sister’s enterprise, Ock Pop Tok. Dr. Phouvieng starting buying a variety of handicrafts; tapestry cotton skirts, jungle vine bags and bamboo paper, and sending them to us. In turn we sent back comments and requests, could the bags be bigger, the paper wider and so on.

Jungle Vine: a non-timber forest product (NTFP) is an eco friendly product, its grows wild in the fields' fallow year and although the process to make yarn is laborious the finished product is an example of great resourcefulness.

Look for the jungle vine bags in our shops.

KATU WEAVER PROJECT

Ethnicity: Katu. Language Group: Mon-Khmer

Province: Salavan Project start date: Jan 2010

The Katu, skilled weavers and cotton growers needed some help re-introducing natural yarns and dyes back into the production of their textiles. As with many communities that have little access to secure markets, the incentive to work with costly materials is low, and weavers turn to cheaper and easier options and start using synthetic materials. Many of our projects start by re-introducing natural fibres and dyes, we buy the product and thus demonstrate that there is value in working with high quality materials.

By invitation of the LNTA our team journeyed to the south to embark on a series of trainings that would build skills and confidence in working with natural yarns and dyes.

Check out the beaded scarves, skirts and home-wares……..uniquely these communities also weave with banana tree fibres…….

AKHA WEAVER PROJECT

Ethnicity: Akha. Language Group: Sino-Tibetan

Province: Phongsaly Project start date: 2003

Cecile Pouget who had moved to a small village with her husband, an EU worker, and their two young sons set project Akha Biladjo up 7 years ago. Cecily needed to do something that was both fulfilling for herself and entertaining for her sons. Working with the Akha women in a nearby village they collectively started stitching kids toys and books out of local fabric. The designs took off and local markets were found, thus was born the Akha Biladjo project a self sustainable way of using traditional skills to generate good steady income. Cecily now lives in Cambodia but the project is self-managed and is one of the success stories of handicraft development in Laos.

The product range continues to grow with initiatives likes Ock Pop Tok requesting new designs and working with the women on new product ranges.

Check out the dolls, necklaces, key chains and other fun fabric animals ……..

TAI DAENG - TAI PUAN WEAVER PROJECT

Ethnicity: Tai Daeng, Tai Puan. Language Group: Tai Kadai

Province: Huaphan, Xieng Khouang Project start date: October 2001

Every now and then a textile so exquisite, so unique shows up on our door step, the first of these was back in 2001, when a trader from Huaphan Province brought to the gallery a long cloth of ikat and supplementary designs. Veo a textile connoisseur was rendered speechless. Ethnologists write that Lao textiles can be traced back to specific villages because the design is so representative of that unique culture or family. We decided to put that theory to test. 5 of us set off for Huaphan, textile in hand looking for the woman that had made this cloth. To cut a long story short we did indeed find that artisan, the connection had been made with a remote community and together we started working on reproducing textiles that took in some cases 6 months to produce. This was how the Village Weaver Projects started.

Now working with dozens of villages in Huaphan, Xieng Khouang Provinces you can see the fruits of these looms….on the walls of our galleries ……see if you can find the reproduction of the textile that set the whole project off………..

HMONG WEAVER PROJECT

Ethnicity: Hmong. Language Group: Mien-Yao

Province: Huaphan, Xieng Khouang Project start date: June 2005

Hemp an almost magical fibre, (the Latin cannabis sativa means useful), is cultivated by the Hmong peoples of Laos. The bark of the plant is used to create cloth and the seeds to make oil. In 2006 we decided to tell the story of hemp in an exhibition at our Fibre2Fabric Gallery. Research trips took us to some of the most isolated mountains in Huaphan Province where we found Hmong communities farming hemp. Using melted bees wax darkened with indigo paste the women draw intricate designs that are then dip dyed in indigo vats to create striking blue and white cloths.

These cloths form the basis for stitch work resulting in cloths that are used for skirts, baby carriers and all manner of items. Here at the gallery you will find the love balls used in the New Year game of pov pob, skirts and repurposed items like pillowcases.

To learn more about hemp visit our Living Crafts Centre, meet Mae Tow Zu Zong a Hmong batik artist.

TAI LUE WEAVER PROJECT

Ethnicity: Tai Lue-North West. Language Group: Tai Kadai

Province: Bokeo, Oudomxai, Sayabouly Project start date: 2009

The Lao National Tourism Administration (LNTA) hired the Ock Pop Tok team to develop handicrafts in their target tourism development villages. The first part of the training is to demonstrate a demand for homespun cotton. The Tai-Lue are experts in cotton growing but skills are waning due to lack of viable options for selling their products. We lead natural dye training programmes followed by product diversity development. The local tourism offices sell their products and often a local market place is created for visiting tourists to stop and support their work through purchases. As you travel around Laos, make a point of stopping in at the local tourism offices to see what activities are being promoted and how you can support the production of local handicrafts.

The fruits of these labours can be seen in items such as cotton elephants from sayabouly, tapestry love gifts and rugs from oudomxai or bags and skirts with colourful motifs from Bokeo.

TAI LUE WEAVER PROJECT

Ethnicity: Tai Lue – Nam Ou. Language Group: Tai Kadai

Province: Luang Namtha, Phongsaly Project start date: February 2001

The Tai Lue of the Nam Ou and Tha waterways are masters of the indigo and stick lack dye (blue & red respectively). Back in the early days, Ock Pop Tok was looking to expand its repertoire of natural dyes and had heard of a village in Nam Bak district, Ban Na Nyang that may potentially be able to help us in that area. On arrival it was instantly apparent that the journey was going to be worth it. The village is a model of traditional cultural life, set in a lush river valley the elegant stilted houses stood over looms, cotton ready for spinning spilled out of baskets and colourful yarns dried in the sun.

Lue villages like Ban Na Nyang posses incredible weaving and dyeing skills but lacked market opportunities, now Na Nyang is a thriving cotton weaving village with many hotels and businesses placing orders. Ock Pop Tok has taken the weavers of Na Nyang to many provinces, their story is inspiring for other weavers to hear.

Look for lengths of naturally dyed fabric or scarves or bags…

PHOU TAI WEAVER PROJECT

Ethnicity: Phou Tai. Language Group: Tai Kadai

Province: Savanakhet Project start date: Jan 2010

The Phou Tai cotton farmers are masters of the ikat technique. Using natural dyes weavers obtain contrasting motifs. Traditional skirt fabric is re-purposed to create home-wares adding diversity to the products range securing better market placement.

TAI MOEI - TAI CHAI WEAVER PROJECT

Ethnicity: Tai Moei and Tai Chai. Language Group: Tai Kadai

Province: Khammouan Project start date:

Tai Moei and Tai Chai weavers in Khammouan keep their traditions alive weaving colourful ikats and ceremonial cloths.

Far far away on the southern borders of Laos and Vietnam Tai Moei and Tai Chai women weave highly colourful and intricate designs. Traditional silk skirts showcase complex ikat motifs with detailed supplementary borders. The ceremonial cloths are unlike any other in Laos, as they are made on 8 pedal and 2 warped looms. These are some of the most remote communities in Laos, weavers produce for barter markets in both Laos and Vietnam. Cloths are influenced by both national cultures with some textiles featuring the Vietnamese language.

Working with Mrs Hua we are developing commercial uses for the unusual ceremonial cloths. Traditional monochrome silk motifs are being made on wider looms creating more potential for new markets and steady cash income. Look for these in the gallery as either hangings or home-ware items. The skirts are impossible to miss……hues of pink, purple and red…

The Ock Pop Tok Shop

The

Ock Pop Tok weaving centre is well worth a visit when in Luang Prabang.