Excerpt: Mr. J.-M. Strobino [1], a knowledgeable French scholar, instrumental in rediscovering and rebuilding Henri Mouhot’s monument, near Luang Prabang, provided the updated knowledge for my follow up story about the Mekong explorers. I am happy to give him credit and to thank him for his kind advises and valuable contribution by sharing his expertise and pictures with GT-Rider.

This iconic photograph was taken by Mr. J.-M. Strobino, in July 1989, when serendipity made him rediscover Henri Mouhot’s monument. Other pictures, and this endeavor’s narration are found in chapter four, hereafter.

Mouhot memorial in July 1989, perforated by a tree.(Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

1. Introduction

Henri Mouhot’s monument is a compelling visit for history and Mekong lovers, and an interesting excursion for Luang Prabang travelers. In itself, this cenotaph is not particularly grandiose, and preliminary information, about the explorer’s life context, will help to appreciate the place’s serenity and to rewind time for one and a half century.

As his grave is far from the beaten path, usual caller might have already read about the great French explorer’s life, his contribution to highlight Angkor Wat to the European world, his prolific research as a naturalist and final lonesome journey from Bangkok to Luang Prabang, exploring part of the Mekong and Nam Khan rivers; the first Westerner to reach that region.

Additional documents can be found online and several travel books, written by 19th century Indo-China adventurers are available as public domain e-documents; they provide enticing readings when visualized in the epoch’s context [14].

This is the link to my first (GT-Rider) write-up about Ban Phanom and the “Mekong explorer’s recollection”:

A Mekong Promenade - part 4: In memoriam of some Mekong explorers

Other Mekong river narratives (GT-Rider’s chapters “bikes on boat” cruises) also refer to the Great River’s exploration and provide additional accounts on similar themes. My complete story is divided into three chapters (only one is already published):

1. A popular Mekong cruise: Houei Xai to Luang Prabang

A popular Mekong cruise: Houai Xai to Luang Prabang

2. Through the Xayaboury dam: Luang Prabang to Pak Lai (to be published next)

3. The empty Mekong: Pak Lai to Vientiane (to be published next)

A fascinating and comprehensive “Henri Mouhot’s grave and monument history” has been written by Mr. J.-M. Strobino [1], it is freely available online, as a pdf e-document. Written in French, it is well illustrated and, as such, also interesting for people less familiar with Molière’s language [2].

Traveling to Luang Prabang is a Southeast Asia bikers’ favorite trip (photographed 27 February 2013)

2. The forgotten explorers

“Henri Mouhot, I Presume?” In May 1867, this could have been Captain Doudard de Lagrée’s address, in Luang Prabang. Unfortunately, his compatriot, explorer and naturalist, passed away, near that city, six year before. Both men had a premature death, as Lagrée expired one year later in Chinese Yunnan and both were hampered to finish their titanic undertakings, a reason why their memories never reached Stanley and Livingstone’s fame. Many scholars will add consideration covering, for instance, the French-Prussian 1870 war's, drawback and the post-colonial era mood and guilt.

Mouhot’s passing, Lagrée’s death and his travel documents’ destruction, with the ensuing controversy about the “Mekong Commission” explorers’ relative merits, hindered their cause in metropolitan France. Garnier, the group’s second in command was recognized by the “British Royal Geographical Society” (award’s listing [4]):

“1870: Patron's Medal - Lieutenant Francis Garnier, for his extensive surveys ... from Cambodia to the Yatig-tsze-Kiang [sic] … and for bringing his expedition to safety after the death of his chief”.

In 1971, together with Livingstone, Garnier was also honored, by the first “World Geographic Congress”.

As for Henri Mouhot, after being rebuffed by his homeland, the same prestigious “British Royal Geographical Society” supported him, for his journeys [8]:

Quoting Garnier, John Keay’s summarizes the epoch’s context [5]:

“Had the Commission been British, London would now be graced with statues of the Mekong pioneers. Their mistake, as Garnier himself wryly put it just before his premature death, lay in being born French.”

The Mekong explorers were not totally forgotten by their homeland. Captain Doudart de Lagrée has a tasteful Khmer style monument in Saint-Vincent-de-Mercuze, his native city [13] and Francis Garnier’s famous statue is erected in Paris, on a boulevard St-Michel’s intersection; this monument also contains his ashes, repatriated from Saigon’s cemetery.

A board mentioning Mouhot’s support by the “London Royal Geographical Society”, as seen at its monument’s site (photographed 27 February 2013)

Luang Prabang, particularly Ban Phanom, the Tai Lue village's neighborhood, is an ideal location to recollect the Mekong pioneers' memory. Henri Mouhot, the first French men to reach the Royal City, passed away on the Nam Khan’s shore, and six years later, the Mekong Commission members also called in that region.

This is Louis de Carné, member of the explorer team, account [6]:

“It was on the banks of the Nam-Kan, not far from the village of Ban-Napao, that the king of Luang-Prabang caused the body of M. Mouhot, who had come there six years before, and had died of fever, to be buried. This traveler had made himself beloved by the natives, who still hold his memory in respect; and the king himself paid a last homage to it, by furnishing, at his own cost, the tomb of our brave countryman.”

A plaque on the monument commemorates its building by captain Lagrée (and his “Mekong Exploration Commission” fellows) and the cenotaph’s reconstructing by August Pavie… was it really in 1887? (See later on in the text)

The commemorative plaque mentioning the date 1887 (really?) (Photographed 14 October 2012)

An engraved wooden board, recently repainted in black with golden characters reminds about the explorers who visited the place and reconstructed the monument. The board should also mention Dr. Neiss, another Indo-China pioneer [14] and, maybe, more recent travelers, who also contributed to the cenotaph’s maintenance; the reference to Guy de Larigaudie, however, is undue in that context [7].

The “In Memoriam” wooden board, the formerly washed out gray panel, has recently been repainted in black (photographed 03 December 2014)

From his first grave, in the sandy Nam Khan river bank, to the rebuilt modern monument, Mouhot’s memorial had a tumultuous history; serendipity more than official dedication kept the cenotaph’s remains and his remembrance alive, till today (see the chronology in chapter four).

After the Pathet Lao army’s arrival in Luang Prabang, in June 1975, and the “People's Democratic Republic of Laos” proclamation, in December 1975, colonial symbols were destroyed or, at best, relegated into oblivion. The Pavie Luang Prabang’s bronze statue, probably ended drowned in the “Great River” and Mouhot’s resting place, without visitors and care, was veiled by the jungle.

Fortunately, for the great explorer’s remembrance, there is a “happy ending” to his memorial saga; in 1989, happenstance had it rediscovered by Mr. J.-M. Strobino, a French writer, historian and traveler (see the story hereafter, in chapter four [1])

3. In Ban Phanom, a dusty trail to the historic site.

My laborious and dusty quest for a French explorer’s burial site is recounted in a previous GT-Rider’s write-up (see reference and link above). I had already travelled to Luang Prabang several times, when, in February 2012, ethnologic curiosity brought me to Ban Phanom, the Tai Lue royal weavers and dancers village. There, I stumbled upon a signboard pointing toward “Henri Mouhot”, a name that I had already spotted, probably in a guidebook. I was unsure, however, what to expect, but decided to follow the dusty road to research the place.

A typical Tai Lue temple in Ban Phanom (photographed 03 February 2012)

The gentle Lue people in Ban Phanom, known for their artistic skills, provided weavings and dance entertainment to Luang Prabang’s royal court. They were also entrusted by August Pavie to maintain Henri Mouhot’s tomb.

Gentle Lue weaver in Ban Phanom

Gentle Lue weaver in Ban Phanom

Year after year, rust takes more tolls on the small metal board pointing along the road, somewhere toward a great explorer’s tomb.

An enigmatic signboard “Henri Mouhot” (photographed 13 October 2012)

A ring road, bypassing Luang Prabang’s center from the northern airport (North Phousi) toward southern Route 13 is in construction since several years. Starting on the Nam Khan’s north rim, it crosses this river on a new bridge, just after Ban Phanom (Phanom village).

During the building work, the whole site was transformed into a lunar style red sand landscape with large trenches carving the hills.

Bypass construction project (photographed 03 February 2012)

Sandy road near the bridge construction site (photographed 13 October 2012)

Luang Prabang's ring road cut through the hills

During my first trip on the new ring road, in February 2012, I was unsure what to expect from a place called “Henri Mouhot” (as beaconed from a metal board), and, naturally, my quest harvested nothing.

Finally, some kilometers down the dusty sand trail, I landed in Ban Prik Noi, another friendly and welcoming Tai Lue village. The dwellers produce Nam Khan riverweed (Khai Paen) and I was invited to sample it, barbecued on an open fire. Travelers to Luang Prabang might try this local specialty which goes particularly well with a “Beer Lao”. [12]

Riverweed production in Ban Prik Noi (photographed 3 February 2012)

Family in Ban Prik Noi (photographed 3 February 2012)

Riverweed barbecue in Ban Prik Noi (photographed 3 February 2012)

Khai Paen (dried riverweed) a North Laos specialty – and Beer Lao (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

Once back home, at my trip’s end, I remembered my fruitless excursion, and after reading some books, I begun to understand what I had missed, somewhere along the Nam Khan’s construction site.

Eight month later, In October 2012, I was back in Luang Prabang, driving on the - still very sandy - trail after Ban Phanom. No signboard, other than the one in the village, pointed toward a “Falang” (foreigner) grave; with rough clues, provided by seldom passer-byes, I finally found a small footway leading to the river’s shore and to an apparently abandoned picnic area.

Unsure about the place, I walked along the stony river bank and, seeing no tomb, gave up the quest again. Fortunately, I had taken some pictures and, in the evening, someone local, commented that I had missed the monument by less than fifty meters.

Still dusty ring road construction site (photographed 13 October 2012).

The “under-construction” bridge over the Nam Khan (photographed 20 May 2014)

Bridge over the Nam Khan (photographed 20 May 2014)

The picnic place (photographed 14 October 2012)

The next morning, I rushed through the dust again and walked down the small pathway to the picnic place.

A little further upstream, hidden in the jungle, I finally stumbled upon the secluded monument; I also realized that I had overseen another foot way, marked with a signboard, and leading uphill to the same place.

The intersection with the pathway down to the river bank (photographed 14 October 2012)

A signboard near to the monument (photographed 27 February 2013)

An uphill trail leading to the monument (photographed 27 February 2013)

Standing in front of Henri Mouhot’s grayish cenotaph, half hidden in the jungle, near to a murmuring river was an appealing and emotional moment. Quiet and peaceful, the place seemed lost in time, forgotten and misunderstood; it felt nor abandoned, nor prized at its historic value.

During that visit, I did not bother about the site’s other “decorative” elements but photographed the concrete statue, overlooking the monument, falsely thinking (as stated in Lonely Planet guidebooks [11]) that it depicted Henri Mouhot. I only learned about my mistake later on, when, showing the photograph to a friend, he recognized August Pavie’s effigy.

Henri Mouhot’s monument and a wooden board featuring some explorers’ names (photographed 14 October 2012)

Henri Mouhot’s cenotaph (photographed 14 October 2012)

Four month later, in October 2013, during a GT-Rider cruise stop-over, I was back to Henri Mouhot’s resting place. Newly cemented stairs had a date engraved, pointing to an upgrading work, in December 2012. The environment had been cleaned; the monuments and other concrete elements were repainted white.

The site’s access, along the Luang Prabang bypass road, was still under-construction, greeting visitors with the same dusty experience.

Intersection with the small pathway leading to the burial site

The cleaned neighborhood and the repainted monument (photographed 03 December 2014)

The newly repainted monument (photographed 27 February 2013)

Luang Prabang is a favorite destination for “GT-Rider” bikers and a compulsory stopover during Mekong river cruises. In February 2014, during a “bikes on boat” sailing, I prompted friends to join me for a call at Henri Mouhot’s burial place. At that time, a woman, at pathway entrance box, requested a small fee from visitors. I reckoned that it was a contribution for the monument, but, not at all, it was just to access the picnic area.

GT-Rider friends visiting Henri Mouhot’s monument (photographed 23 February 2014)

A small booth collecting entrance fees (photographed 23 February 2014)

I paid some additional visits to Ban Phanom, to the Nam Khan’s peaceful shore and to Henri Mouhot’s monument, and, every time noticed small changes. The ticket booth had been removed, a signboard was fixed near the pathway’s entrance and the picnic place has been cleaned.

During my last visit, in December 2014, I wondered why a plasticized foreigner’s photograph, decorated with a French flag ribbon, had been left at the monument’s foot. A new stair had also been engraved with the date: “29.11.2014”.

A new date engraved in a freshly cemented stair text (photographed 3 December 2014)

Several other elements made not sense to me, but, without additional information, I shun to clarify them. Searches online shed few lights on my questions and I would never imagine that, beyond its historic and romantic value, this place had lived a saga of striking changes.

After my GT-Rider write-up publication (“In memoriam of some Mekong explorers”), an unexpected message reached my inbox. I was pleased to be contacted by Mr. J.-M. Strobino [1], a respected Laos scholar who, in 1989, rediscovered Henri Mouhot’s monument, and was instrumental to its rehabilitation. In a particularly comprehensive and enticing account, he describes the cenotaph’s hectic history, a worthwhile chronicle to understand the shrine and to make its visit even more valuable.

4. History of Henri Mouhot’s burial place.

(based on : J-M Strobino “HISTOIRE DE LA SÉPULTURE D’HENRI MOUHOT ET DE SON MONUMENT FUNÉRAIRE 1861-1990” [2])

Mr. Strobino clarifies, at its chronicle beginning, that the brick and plaster construction, erected near the Nam Khan shores is actually not Henri Mouhot’s grave, but a memorial to the great explorer, a cenotaph. The burial place itself was not far away; closer to the river, his loyal servants dug it in a sandy and malleable ground.

When captain Lagrée and the “Mekong Exploration Commission” members called in the region, in May 1867, they got a royal permission to erect a shrine, but, to avoid disturbing the deceased spirit, were hampered to excavate his remains, which, most probably, had anyway been washed anyway by floods [6].

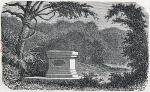

The first monument, designed and pictures by Louis Delaporte, a Mekong Expedition Commission’s member.

Photo credit : Mouhot_-_Voyage_dans_les_royaumes_de_Siam,_de_Cambodge,_de_Laos_et_autres_parties_centrales_de_l'Indo-Chine,_éd._Lanoye,_1868,_planche_28

Mr. Strobino’s fascinating account of “Henri Mouhot’s burial place and monument history 1861-1990” is an extremely well documented research, loaded with appealing illustrations. Despite being only available in French, it is an enticing document, even for readers unfamiliar with that language, for its visual content. The story’s full “pdf document” [2], can be downloaded from the following link:

https://drive.google.com/folderview?id=0B3CKad015OMXaWZqVHk3QzdhUkU&usp=sharing

This is a summarized chronology extracted from this comprehensive document.

1861, November 10. Henri Mouhot’s passing date, on the Nam Khan’s shores, and burial by his two loyal servants.

The explorer’s last moments, together with a complete account of his peregrination to Angkor, Bangkok and finally to Luang Prabang can be read in his book available (in French or English) as a free public domain download [12]]

1867, May 10: After calling in Luang Prabang and getting a royal permission, captain Doudart de Lagrée and the “Mekong Exploration Commission” members, built a permanent monument.

1883, July 27: Dr. Neis sojourned in Luang Prabang and described the catastrophic situation of the memorial, with only some bricks remaining in place. Without the means to repair it, he just marked the spot with a wooden cross.

1887-1890: August Pavie has the monument rebuilt in bricks and stones, adorned with two marble plaques on its long sides.

The board’s date, showing Pavie’s restauration, was stated as 1887; after the publication of Mr. Strobino’s historic research [2], the French Embassy, however, had it corrected to the precise rehabilitation year, which is 1890. Aware visitors can spot the former engraved numerals under the new painting.

Close up of the corrected date on the rear plaque (photographed 27.02.2013)

1890-1950: After Pavie’s restauration, the cenotaph is frequently visited by Luang Prabang travelers and it is mentioned in guides and travel accounts, finally it falls into oblivion.

1950- 1986: Period of successive rehabilitations and abandonments. Neglected during the Japanese occupation, the monument is restored in 1951 by “The French School of Asian Studies (EFEO)”. In 1954, after their Dien Bien Phu defeat, the French leave Indochina and the interest for the memorial vanishes.

During the second Indochina war, Luang Prabang’s region, close to the Pathet Lao influence zone, became a strategically dangerous sector, and only one visitor’s account was published during that time.

1975: After the Pathet Lao sized power in Vientiane and proclaimed the “ Lao People's Democratic Republic”, the country closed itself to visitors and Mouhot’s monument was again taken over by the jungle vegetation.

This could have been the definitive cenotaph’s demise, had incidental events not decided differently.

Beginning in 1986, a new opening policy, allowed more foreigners to visit the socialist republic. In 1988, Mr. Jean-Michel Strobino, was among the first French citizen to enter Laos again, in order to complete guides about the former Indochina countries.

A second trip, in July 1989, brought him to the sleepy Luang Prabang, together with his friend and guide Mongkhol Sasorith, a local scholar, expert in Laos’ history. In a casual discussion, his companion told him about the explorer Henri Mouhot, his extraordinary adventure and tragic fate in the neighborhood.

Curious to find out more, the two friends started a quest, which lead them, by jeep first, near to the Nam Khan’s banks. After hiking for several hours, crisscrossing through jungle vegetation and mud, they suddenly stumbled upon a monument. It was Henri Mouhot’s cenotaph, in a pathetic state of nature degradation and human profanation.

Mr. Strobino hiking (with his friend) through a muddy jungle (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

These are additional pictures, to the iconic “tree skewered cenotaph” view (see at the text’s beginning), taken by Mr. Strobino in July 1989. All photographs courtesy Mr. Jean-Michel Strobino.

Rear view of the deteriorated cenotaph (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

Rear plaque with a perforation through the whole monument (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino )

Standing in front of the wrecked, albeit still solemn, monument, was a deeply emotional moment for the two friends; a prize for their arduous endeavor and the pride to rediscovering a great man’s memorial.

Mr. Strobino and his friend, Mr. Mongkhol Sasorith, in front of the monument (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

Apart from taking documentary pictures, there was nothing else to be done immediately. With some meager flowers, from the neighborhood, Mr. Strobino decorated the cenotaph and, after a last homage to Henri Mouhot’s memory, the pair returned to Luang Prabang.

A small flower decoration in homage to Henri Mouhot’s memory (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

Back in Vientiane, and before leaving Laos, Mr. Strobino shared his discovering with the French ambassador, and, in France, alerted the authorities of Montbéliard, Mouhot’s native city. His pictures documented the monument’s destruction and the urgency of a rehabilitation.

Answers, from all sides, where kindhearted; the French Embassy, in Vientiane, rapidly commanded the renovation work and, on 25th May 1990, the cenotaph was totally renovated and its neighborhood had been cleaned.

As a token to its courageous citizen, Montbéliard authorities had a marble plate engraved by a local craftsmen, Mr. Maurice Bloch. The 6,8 kg heavy piece was then shipped to Laos in order to be affixed to the cenotaph. Meanwhile, during another visit to Luang Prabang, in July 1990, Mr. Strobino organized a small inauguration ceremony for the renovated monument. He carried an official thankful missive from Montbéliard’s mayor, read it publicly at that occasion, and, later on, handed it over to the Lao minister of culture.

The plaque offered by the Montbéliard municipality, affixed in September 1990 (photographed 27 February 2013):

M. Jean-Michel Strobino during a visit to the restored monument (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

Mr. Strobino paying homage to Henri Mouhot’s memory with some flowers (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

5. Still an unsettled ending

This could be Henri Mouhot burial place’s saga denouement, the memorial’s happy end. After its rehabilitation, and the homage by the Montbéliard citizens, the year 1990, is also when Mr. Strobino concludes his account [2].

More then twenty years later, during my initial visit to the site, in 2012, I had mixed feelings. A dilapidated picnic place, greyish stones, faded engravings and untamed vegetation, produced an abandonment sense, not without charm, in the quiet jungle environment.

Some “decorative” elements, however felt odd. A French style road stone indicated “kilometer zero (lak soon)” and a concrete elephant was fossilized in a never-ending smile. I only understood later that these peculiarities resulted from a private initiative, without any symbolism or link to the explorer’s memory.

“Lak soon – kilometer zero” road stone freshly repainted, on Mouhot’s site (photographed 27 February 2013):

An ever-smiling concrete elephant statue (photographed 27 February 2013)

Another baffling item is a concrete effigy, often confused with Henri Mouhot itself, as in Lonely Planet guidebooks [11]:

« … His heavily bearded statue at the site looks altogether more cheerful … »

Actually, it represents August Pavie, whose bronze statues’ fate, in Laos, are another saga. This figure, however, is only a rough concrete copy.

Having Pavie watching over Mouhot’s memorial is not the worst discrepancy, but, as this is again a private initiative, there is no clear and harmonious integration. It is anyway inappropriate to deposit private and irrelevant elements on a shrine site.

Pavie’s concrete effigy, adorned with wasp nests, on Henri Mouhot’s site (photographed 14 October 2012)

Pavie’s concrete statue, cleaned (photographed 27 February 2013)

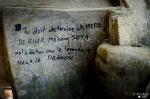

Non-sense graffiti on August Pavie’s statue (photographed 27 February 2013)

August Pavie’s concrete statue overlooking Henri Mouhot’s monument, another graffiti is written in its back (photographed 27 February 2013)

After the 1975 Pathet Lao forces arrival, Luang Prabang’s original Pavie bronze statue fall into disgrace, and was probably drown in the Mekong, or hidden somewhere. The embassy garden, in Vientiane, still hosts the other “original”, it is concealed, from general public sights, by the residence’s walls.

French embassy, Vientiane – August Pavie’s original bronze effigy by the French sculptor Paul Ducuing (photographed 25 May 2014)

The historic and commemorative value of Henri Mouhot’s burial place, on the the Nam Khan’s bank , resides in its solemnity, integrity and authenticity, which, in the same way that Luang Prabang’s heritage is protected by UNESCO, should be kept undisturbed for future generations. The Disneyesque concrete elements, deposited on the site, should be removed and put to better use, maybe along the picnic place.

In addition to maintenance and cleanings efforts, at Henri Mouhot’s memorial place, I noticed, during a December 2014 visit, a plasticized picture, adorned with a French flag ribbon. Here, again, I got a clue from Mr. Strobino, who was befriended with the depicted person: Pierre Mouhot, a fifth generation descendant of the explorer.

A plasticized Pierre Mouhot picture, a descendant of the explorer (photographed 3 December 2014)

Pierre Mouhot's picture and a small plaque at it's ancestor's burial place (picture courtesy J.-M. Strobino)

Pierre Mouhot was an active member of “Le Frangipanier” [8] a small humanitarian organisation operating in healthcare, education and cultural preservation. He passed away, in November 2013, at the early age of fifty-eight. Fulfilling his wishes, his widow had his ashes dispersed on his ancestor’s burial site. The ceremony was held on 5th August 2014, in the French ambassador’s presence and with local authorities.

Reminding August Pavie’s arrangement, with Ban Phanom’s inhabitant, to maintain the deceased explorer’s monument, His Excellency renewed the commitment, with Ban Noun Savath’s leader, to preserve the cenotaph; nowadays it is located on that village’s territory [10].

The rear monument’s plaque with the date corrected by the French Embassy (Photographed 27 February 2013)

6. Epilogue

Mr. Strobino’s additional information, about Henri Mouhot and its monument’s history, as well as readings about the Great Rivers’ exploration, have enhanced my sympathy and appreciation for that region. In itself, the Luang Prabang’s ring road completion, might not entice more visitors to the Nam Khan’s bank, informed travelers, however, will find it easier to call at the explorer’s burial place. As stated at my write-up’s beginning, there is nothing magnificent to the cenotaph itself; its beauty is in the site’s emotional value, a powerful means to recollect the past, a help to understand the present days.

Despite the progressing Laos modernization, the former jungle treks’ pavement to avoid Luang Prabang’s city center, the traditional Lue bamboo and wooden stilt houses replacement by concrete constructions, motorized vehicles instead of elephants and oxcarts, along with ubiquitous TV antennas, few things have really changed since the explorer’s times.

This is how Jules Roy describes the Nam Khan, as is flows, facing Henri Mouhot’s burial place (translate from the French text) [8]:

“On the opposite site, a dark boulders’ wall marks the torrent’s other rim: no dwelling, no human signs in the neighborhood. Only, from time to time, a light pirogue will cruise in front of this resting place, and the Laotian bargeman will glimpse with respect, maybe with fear, to this sad and touching memorial …”

The rocky Nam Khan in front of Henri Mouhot’s resting place (photographed 20 May 2014)

Traditional fishermen’s boats in Ban Phanom (photographed 24 February 2014)

A banyan tree, near Henri Mouhot’s monument

The classic and moody “Henri Mouhot’s last bivouac” engraving (published in “Le Tour du Monde” [14])

-----------------------

NOTES :

[1] Mr. Jean-Michel STROBINO is Nice city’s «Historic Heritage Center» Director. Historian and writer, he has intensively travelled off the beaten tracks, hiking, for instance, through a large part of the Himalayas. His interests also brought him to Indochina were he got enticed to research the exploration pioneer history. He wrote an Himalaya trekking guide and the first, French language, Vietnam guidebook.

In 1989, during a mission in Laos and by serendipity, he rediscovered Henri Mouhot’s monument, near Ban Phanom, and was instrumental its rehabilitation.

Mr. J.-M. Strobino’s publications listing:

Books:

Guide du Vietnam, Alticoop éditions, Nice, 1989

Vietnam, guida turistica, Calderini, Bologna, 1990 (en italien)

Himalaya, guide de trekking, Apsara éditions, 1992

Légendes du Laos, White Lotus Press, Bangkok, 2013 (traduction française)

Published papers :

Laos, le chemin de fer des canonnières, La Vie du Rail, n°2329, Janvier 1992

Histoire de la sépulture d’Henri Mouhot et de son monument funéraire 1861-1990, Bulletin de la Société d’Histoire Naturelle du Pays de Montbéliard, 2013, p.197-224

Peter Hauff, les aventures d’un marchand norvégien en Indochine au début du XXème siècle, Les Hors-Série de l’AICTPL, n°5, Juin 2013

Camoens, les Lusiades et le Mékong «portugais», Revue Philao, n°96, 3ème trimestre 2014, p. 22-27

André Escoffier, un autre poète (trop peu connu) du Laos, Revue Philao, n°98, 1er trimestre 2015, p. 23-27

Le commandant Diacre, un héros oublié du Mékong, Revue Philao, n°100

These papers can be downloaded in .pdf from the following link : ……………..

[2] The 150th anniversary of Henri Mouhot’s passing was commemorated, in 2011, in his native Montbéliard city. At that occasion, a French post stamp, with his effigy, was published.

J.-M. Strobino also contributed to the explorers’ remembrance with a particularly well documented and interesting write-up: “1861-1990, Histoire de la sépulture d’Henri Mouhot et de son monument funéraire”.

This document, in French but well illustrated, is available through the following link:

JM Strobino

Henri Mouhot’s commemorative post stamp

[3] This write-up is not about Henri Mouhot’s life, but mostly centered on his monument’s history. Information about the explorer’s life can be read in his travel account and in various online documents, for instance in Wikipedia:

Henri Mouhot - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

[4] Royal Society gold award - pdf listing (accessed and downloaded online): GoldMedallists18322011.pdf

In 1873, Stanley also got the “Patron's Medal - Henry Morton Stanley For his Relief of Livingstone, and for bringing his valuable journal and papers to England

[5] Mad About the Mekong: Exploration and Empire in South East Asia

John Keay

HarperCollins E-Books - Kindle Edition

[6] Travels on the Mekong, Cambodia, Laos and Yunnan

Louis de Carné

White Lotus, Bangkok, 1995

[7] Guy de Larigaudie was a French scout and traveler. In 1937/1938 he achieved the first link, by car, between Paris and Saigon, and, at that occasion passed Luang Prabang. Other than this, he is unrelated to Mouhot’s cenotaph or to the Mekong river exploration.

Guy de Larigaudie — Wikipédia

[8] Les Franc-Comtois en Orient – Henri Mouhot Premier Explorateur du Laos

Jules Roy

Dole Vernier-Arcelin, Editeur, 1884

Extract:

“Il fit part de ses projets d'abord à une société française qui ne lui offrit aucun secours, puis au gouvernement de l'Empereur qui lui refusa même le passage gratuit à bord de ses vaisseaux; mais les sociétés de géographie et de zoologie de Londres approuvèrent entièrement le plan de son expédition et l’aidèrent puissamment à l’exécuter”

….

“En face s'élève un mur de roches noirâtres qui forme l'autre rive du torrent : nulle habitation, nulle trace humaine aux alentours. Seule parfois une pirogue légère passera devant ce lieu de repos, et le batelier laotien regardera avec respect, peut-être avec effroi, ce souvenir triste et touchant du passage d'un homme de bien qui est tombé en précurseur de notre civilisation, en éclaireur de notre drapeau, à cinq mille lieues de sa patrie, à quatre cents du point le plus rapproché qu'habite un Européen!”

[9] Pierre Mouhot

Le Frangipanier - Éducation, formation professionnelle, culture et préservation du patrimoine

Villa Sisavad - Ban Sisavad Neua District Chanthabouly - Vientiane

[email protected]

[10] Pierre Mouhot’s ceremony in Luang Prabang with the French Ambassador (August 2014):

Déplacement de l’Ambassadeur à Luang Prabang

Le discours de l’Ambassadeur

La lettre de Pierre Mouhot adressée à son ancêtre Henri, lue par son épouse à cette occasion.

[11] Lonely Planet, Laos travel guides, 7th Edition, Dec 2010 and 8th Edition February 2014

Lonely Planet, however, is not the only publication to make the Pavie-Mouhot statue confusion, an uninformed visit undoubtedly leads to such a disorientation

[12] Captain Ernest Doudard de Lagrée

Ernest Doudart de Lagrée — Wikipédia

Histoire du monument dédié à Doudart de Lagrée

[13] Francis Garnier (second in command)

Francis Garnier, explorateur de l'Indochine et la confrontation Ferry, Clemenceau - Images du globe : histoire et sociologie politiques de ses représentations publiques

Monument à Francis Garnier — Wikipédia

GARNIER Francis (1839-1873) - Cimetières de France et d'ailleurs

Saint-Etienne-Hanoï-Paris: Francis Garnier

[14] Some public domain books about Laos and the Mekong exploration:

Henri Mouhot: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/46559/46559-h/46559-h.htm

Travels in the central parts of Indochina (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos, during the years 1858, 1859, and 1860, Henri Mouhot, Charles Mouhot, Murray publisher, 1864

In two volumes, Google books, public domain E-Book

Dr. Neiss book: Le Tour du monde : nouveau journal des voyages / publié sous la direction de M. Édouard Charton et illustré par nos plus célèbres artistes

Francis Garnier

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k58356827.r=Voyage+d'exploration+en+Indochine+Francis+Garnier.langFR

Travels in Indo-China and the Chinese Empire

Louis de Carné

Chapman and Hall, 1872

Free Google eBook

A signboard inviting travelers to visit Henri Mouhot’s monument on the Nam Khan’s bank.

A signboard inviting travelers to visit Henri Mouhot’s monument on the Nam Khan’s bank.

This iconic photograph was taken by Mr. J.-M. Strobino, in July 1989, when serendipity made him rediscover Henri Mouhot’s monument. Other pictures, and this endeavor’s narration are found in chapter four, hereafter.

Mouhot memorial in July 1989, perforated by a tree.(Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

1. Introduction

Henri Mouhot’s monument is a compelling visit for history and Mekong lovers, and an interesting excursion for Luang Prabang travelers. In itself, this cenotaph is not particularly grandiose, and preliminary information, about the explorer’s life context, will help to appreciate the place’s serenity and to rewind time for one and a half century.

As his grave is far from the beaten path, usual caller might have already read about the great French explorer’s life, his contribution to highlight Angkor Wat to the European world, his prolific research as a naturalist and final lonesome journey from Bangkok to Luang Prabang, exploring part of the Mekong and Nam Khan rivers; the first Westerner to reach that region.

Additional documents can be found online and several travel books, written by 19th century Indo-China adventurers are available as public domain e-documents; they provide enticing readings when visualized in the epoch’s context [14].

This is the link to my first (GT-Rider) write-up about Ban Phanom and the “Mekong explorer’s recollection”:

A Mekong Promenade - part 4: In memoriam of some Mekong explorers

Other Mekong river narratives (GT-Rider’s chapters “bikes on boat” cruises) also refer to the Great River’s exploration and provide additional accounts on similar themes. My complete story is divided into three chapters (only one is already published):

1. A popular Mekong cruise: Houei Xai to Luang Prabang

A popular Mekong cruise: Houai Xai to Luang Prabang

2. Through the Xayaboury dam: Luang Prabang to Pak Lai (to be published next)

3. The empty Mekong: Pak Lai to Vientiane (to be published next)

A fascinating and comprehensive “Henri Mouhot’s grave and monument history” has been written by Mr. J.-M. Strobino [1], it is freely available online, as a pdf e-document. Written in French, it is well illustrated and, as such, also interesting for people less familiar with Molière’s language [2].

Traveling to Luang Prabang is a Southeast Asia bikers’ favorite trip (photographed 27 February 2013)

2. The forgotten explorers

“Henri Mouhot, I Presume?” In May 1867, this could have been Captain Doudard de Lagrée’s address, in Luang Prabang. Unfortunately, his compatriot, explorer and naturalist, passed away, near that city, six year before. Both men had a premature death, as Lagrée expired one year later in Chinese Yunnan and both were hampered to finish their titanic undertakings, a reason why their memories never reached Stanley and Livingstone’s fame. Many scholars will add consideration covering, for instance, the French-Prussian 1870 war's, drawback and the post-colonial era mood and guilt.

Mouhot’s passing, Lagrée’s death and his travel documents’ destruction, with the ensuing controversy about the “Mekong Commission” explorers’ relative merits, hindered their cause in metropolitan France. Garnier, the group’s second in command was recognized by the “British Royal Geographical Society” (award’s listing [4]):

“1870: Patron's Medal - Lieutenant Francis Garnier, for his extensive surveys ... from Cambodia to the Yatig-tsze-Kiang [sic] … and for bringing his expedition to safety after the death of his chief”.

In 1971, together with Livingstone, Garnier was also honored, by the first “World Geographic Congress”.

As for Henri Mouhot, after being rebuffed by his homeland, the same prestigious “British Royal Geographical Society” supported him, for his journeys [8]:

Quoting Garnier, John Keay’s summarizes the epoch’s context [5]:

“Had the Commission been British, London would now be graced with statues of the Mekong pioneers. Their mistake, as Garnier himself wryly put it just before his premature death, lay in being born French.”

The Mekong explorers were not totally forgotten by their homeland. Captain Doudart de Lagrée has a tasteful Khmer style monument in Saint-Vincent-de-Mercuze, his native city [13] and Francis Garnier’s famous statue is erected in Paris, on a boulevard St-Michel’s intersection; this monument also contains his ashes, repatriated from Saigon’s cemetery.

A board mentioning Mouhot’s support by the “London Royal Geographical Society”, as seen at its monument’s site (photographed 27 February 2013)

Luang Prabang, particularly Ban Phanom, the Tai Lue village's neighborhood, is an ideal location to recollect the Mekong pioneers' memory. Henri Mouhot, the first French men to reach the Royal City, passed away on the Nam Khan’s shore, and six years later, the Mekong Commission members also called in that region.

This is Louis de Carné, member of the explorer team, account [6]:

“It was on the banks of the Nam-Kan, not far from the village of Ban-Napao, that the king of Luang-Prabang caused the body of M. Mouhot, who had come there six years before, and had died of fever, to be buried. This traveler had made himself beloved by the natives, who still hold his memory in respect; and the king himself paid a last homage to it, by furnishing, at his own cost, the tomb of our brave countryman.”

A plaque on the monument commemorates its building by captain Lagrée (and his “Mekong Exploration Commission” fellows) and the cenotaph’s reconstructing by August Pavie… was it really in 1887? (See later on in the text)

The commemorative plaque mentioning the date 1887 (really?) (Photographed 14 October 2012)

An engraved wooden board, recently repainted in black with golden characters reminds about the explorers who visited the place and reconstructed the monument. The board should also mention Dr. Neiss, another Indo-China pioneer [14] and, maybe, more recent travelers, who also contributed to the cenotaph’s maintenance; the reference to Guy de Larigaudie, however, is undue in that context [7].

The “In Memoriam” wooden board, the formerly washed out gray panel, has recently been repainted in black (photographed 03 December 2014)

From his first grave, in the sandy Nam Khan river bank, to the rebuilt modern monument, Mouhot’s memorial had a tumultuous history; serendipity more than official dedication kept the cenotaph’s remains and his remembrance alive, till today (see the chronology in chapter four).

After the Pathet Lao army’s arrival in Luang Prabang, in June 1975, and the “People's Democratic Republic of Laos” proclamation, in December 1975, colonial symbols were destroyed or, at best, relegated into oblivion. The Pavie Luang Prabang’s bronze statue, probably ended drowned in the “Great River” and Mouhot’s resting place, without visitors and care, was veiled by the jungle.

Fortunately, for the great explorer’s remembrance, there is a “happy ending” to his memorial saga; in 1989, happenstance had it rediscovered by Mr. J.-M. Strobino, a French writer, historian and traveler (see the story hereafter, in chapter four [1])

3. In Ban Phanom, a dusty trail to the historic site.

My laborious and dusty quest for a French explorer’s burial site is recounted in a previous GT-Rider’s write-up (see reference and link above). I had already travelled to Luang Prabang several times, when, in February 2012, ethnologic curiosity brought me to Ban Phanom, the Tai Lue royal weavers and dancers village. There, I stumbled upon a signboard pointing toward “Henri Mouhot”, a name that I had already spotted, probably in a guidebook. I was unsure, however, what to expect, but decided to follow the dusty road to research the place.

A typical Tai Lue temple in Ban Phanom (photographed 03 February 2012)

The gentle Lue people in Ban Phanom, known for their artistic skills, provided weavings and dance entertainment to Luang Prabang’s royal court. They were also entrusted by August Pavie to maintain Henri Mouhot’s tomb.

Gentle Lue weaver in Ban Phanom

Gentle Lue weaver in Ban Phanom

Year after year, rust takes more tolls on the small metal board pointing along the road, somewhere toward a great explorer’s tomb.

An enigmatic signboard “Henri Mouhot” (photographed 13 October 2012)

A ring road, bypassing Luang Prabang’s center from the northern airport (North Phousi) toward southern Route 13 is in construction since several years. Starting on the Nam Khan’s north rim, it crosses this river on a new bridge, just after Ban Phanom (Phanom village).

During the building work, the whole site was transformed into a lunar style red sand landscape with large trenches carving the hills.

Bypass construction project (photographed 03 February 2012)

Sandy road near the bridge construction site (photographed 13 October 2012)

Luang Prabang's ring road cut through the hills

During my first trip on the new ring road, in February 2012, I was unsure what to expect from a place called “Henri Mouhot” (as beaconed from a metal board), and, naturally, my quest harvested nothing.

Finally, some kilometers down the dusty sand trail, I landed in Ban Prik Noi, another friendly and welcoming Tai Lue village. The dwellers produce Nam Khan riverweed (Khai Paen) and I was invited to sample it, barbecued on an open fire. Travelers to Luang Prabang might try this local specialty which goes particularly well with a “Beer Lao”. [12]

Riverweed production in Ban Prik Noi (photographed 3 February 2012)

Family in Ban Prik Noi (photographed 3 February 2012)

Riverweed barbecue in Ban Prik Noi (photographed 3 February 2012)

Khai Paen (dried riverweed) a North Laos specialty – and Beer Lao (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

Once back home, at my trip’s end, I remembered my fruitless excursion, and after reading some books, I begun to understand what I had missed, somewhere along the Nam Khan’s construction site.

Eight month later, In October 2012, I was back in Luang Prabang, driving on the - still very sandy - trail after Ban Phanom. No signboard, other than the one in the village, pointed toward a “Falang” (foreigner) grave; with rough clues, provided by seldom passer-byes, I finally found a small footway leading to the river’s shore and to an apparently abandoned picnic area.

Unsure about the place, I walked along the stony river bank and, seeing no tomb, gave up the quest again. Fortunately, I had taken some pictures and, in the evening, someone local, commented that I had missed the monument by less than fifty meters.

Still dusty ring road construction site (photographed 13 October 2012).

The “under-construction” bridge over the Nam Khan (photographed 20 May 2014)

Bridge over the Nam Khan (photographed 20 May 2014)

The picnic place (photographed 14 October 2012)

The next morning, I rushed through the dust again and walked down the small pathway to the picnic place.

A little further upstream, hidden in the jungle, I finally stumbled upon the secluded monument; I also realized that I had overseen another foot way, marked with a signboard, and leading uphill to the same place.

The intersection with the pathway down to the river bank (photographed 14 October 2012)

A signboard near to the monument (photographed 27 February 2013)

An uphill trail leading to the monument (photographed 27 February 2013)

Standing in front of Henri Mouhot’s grayish cenotaph, half hidden in the jungle, near to a murmuring river was an appealing and emotional moment. Quiet and peaceful, the place seemed lost in time, forgotten and misunderstood; it felt nor abandoned, nor prized at its historic value.

During that visit, I did not bother about the site’s other “decorative” elements but photographed the concrete statue, overlooking the monument, falsely thinking (as stated in Lonely Planet guidebooks [11]) that it depicted Henri Mouhot. I only learned about my mistake later on, when, showing the photograph to a friend, he recognized August Pavie’s effigy.

Henri Mouhot’s monument and a wooden board featuring some explorers’ names (photographed 14 October 2012)

Henri Mouhot’s cenotaph (photographed 14 October 2012)

Four month later, in October 2013, during a GT-Rider cruise stop-over, I was back to Henri Mouhot’s resting place. Newly cemented stairs had a date engraved, pointing to an upgrading work, in December 2012. The environment had been cleaned; the monuments and other concrete elements were repainted white.

The site’s access, along the Luang Prabang bypass road, was still under-construction, greeting visitors with the same dusty experience.

Intersection with the small pathway leading to the burial site

The cleaned neighborhood and the repainted monument (photographed 03 December 2014)

The newly repainted monument (photographed 27 February 2013)

Luang Prabang is a favorite destination for “GT-Rider” bikers and a compulsory stopover during Mekong river cruises. In February 2014, during a “bikes on boat” sailing, I prompted friends to join me for a call at Henri Mouhot’s burial place. At that time, a woman, at pathway entrance box, requested a small fee from visitors. I reckoned that it was a contribution for the monument, but, not at all, it was just to access the picnic area.

GT-Rider friends visiting Henri Mouhot’s monument (photographed 23 February 2014)

A small booth collecting entrance fees (photographed 23 February 2014)

I paid some additional visits to Ban Phanom, to the Nam Khan’s peaceful shore and to Henri Mouhot’s monument, and, every time noticed small changes. The ticket booth had been removed, a signboard was fixed near the pathway’s entrance and the picnic place has been cleaned.

During my last visit, in December 2014, I wondered why a plasticized foreigner’s photograph, decorated with a French flag ribbon, had been left at the monument’s foot. A new stair had also been engraved with the date: “29.11.2014”.

A new date engraved in a freshly cemented stair text (photographed 3 December 2014)

Several other elements made not sense to me, but, without additional information, I shun to clarify them. Searches online shed few lights on my questions and I would never imagine that, beyond its historic and romantic value, this place had lived a saga of striking changes.

After my GT-Rider write-up publication (“In memoriam of some Mekong explorers”), an unexpected message reached my inbox. I was pleased to be contacted by Mr. J.-M. Strobino [1], a respected Laos scholar who, in 1989, rediscovered Henri Mouhot’s monument, and was instrumental to its rehabilitation. In a particularly comprehensive and enticing account, he describes the cenotaph’s hectic history, a worthwhile chronicle to understand the shrine and to make its visit even more valuable.

4. History of Henri Mouhot’s burial place.

(based on : J-M Strobino “HISTOIRE DE LA SÉPULTURE D’HENRI MOUHOT ET DE SON MONUMENT FUNÉRAIRE 1861-1990” [2])

Mr. Strobino clarifies, at its chronicle beginning, that the brick and plaster construction, erected near the Nam Khan shores is actually not Henri Mouhot’s grave, but a memorial to the great explorer, a cenotaph. The burial place itself was not far away; closer to the river, his loyal servants dug it in a sandy and malleable ground.

When captain Lagrée and the “Mekong Exploration Commission” members called in the region, in May 1867, they got a royal permission to erect a shrine, but, to avoid disturbing the deceased spirit, were hampered to excavate his remains, which, most probably, had anyway been washed anyway by floods [6].

The first monument, designed and pictures by Louis Delaporte, a Mekong Expedition Commission’s member.

Photo credit : Mouhot_-_Voyage_dans_les_royaumes_de_Siam,_de_Cambodge,_de_Laos_et_autres_parties_centrales_de_l'Indo-Chine,_éd._Lanoye,_1868,_planche_28

Mr. Strobino’s fascinating account of “Henri Mouhot’s burial place and monument history 1861-1990” is an extremely well documented research, loaded with appealing illustrations. Despite being only available in French, it is an enticing document, even for readers unfamiliar with that language, for its visual content. The story’s full “pdf document” [2], can be downloaded from the following link:

https://drive.google.com/folderview?id=0B3CKad015OMXaWZqVHk3QzdhUkU&usp=sharing

This is a summarized chronology extracted from this comprehensive document.

1861, November 10. Henri Mouhot’s passing date, on the Nam Khan’s shores, and burial by his two loyal servants.

The explorer’s last moments, together with a complete account of his peregrination to Angkor, Bangkok and finally to Luang Prabang can be read in his book available (in French or English) as a free public domain download [12]]

1867, May 10: After calling in Luang Prabang and getting a royal permission, captain Doudart de Lagrée and the “Mekong Exploration Commission” members, built a permanent monument.

1883, July 27: Dr. Neis sojourned in Luang Prabang and described the catastrophic situation of the memorial, with only some bricks remaining in place. Without the means to repair it, he just marked the spot with a wooden cross.

1887-1890: August Pavie has the monument rebuilt in bricks and stones, adorned with two marble plaques on its long sides.

The board’s date, showing Pavie’s restauration, was stated as 1887; after the publication of Mr. Strobino’s historic research [2], the French Embassy, however, had it corrected to the precise rehabilitation year, which is 1890. Aware visitors can spot the former engraved numerals under the new painting.

Close up of the corrected date on the rear plaque (photographed 27.02.2013)

1890-1950: After Pavie’s restauration, the cenotaph is frequently visited by Luang Prabang travelers and it is mentioned in guides and travel accounts, finally it falls into oblivion.

1950- 1986: Period of successive rehabilitations and abandonments. Neglected during the Japanese occupation, the monument is restored in 1951 by “The French School of Asian Studies (EFEO)”. In 1954, after their Dien Bien Phu defeat, the French leave Indochina and the interest for the memorial vanishes.

During the second Indochina war, Luang Prabang’s region, close to the Pathet Lao influence zone, became a strategically dangerous sector, and only one visitor’s account was published during that time.

1975: After the Pathet Lao sized power in Vientiane and proclaimed the “ Lao People's Democratic Republic”, the country closed itself to visitors and Mouhot’s monument was again taken over by the jungle vegetation.

This could have been the definitive cenotaph’s demise, had incidental events not decided differently.

Beginning in 1986, a new opening policy, allowed more foreigners to visit the socialist republic. In 1988, Mr. Jean-Michel Strobino, was among the first French citizen to enter Laos again, in order to complete guides about the former Indochina countries.

A second trip, in July 1989, brought him to the sleepy Luang Prabang, together with his friend and guide Mongkhol Sasorith, a local scholar, expert in Laos’ history. In a casual discussion, his companion told him about the explorer Henri Mouhot, his extraordinary adventure and tragic fate in the neighborhood.

Curious to find out more, the two friends started a quest, which lead them, by jeep first, near to the Nam Khan’s banks. After hiking for several hours, crisscrossing through jungle vegetation and mud, they suddenly stumbled upon a monument. It was Henri Mouhot’s cenotaph, in a pathetic state of nature degradation and human profanation.

Mr. Strobino hiking (with his friend) through a muddy jungle (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

These are additional pictures, to the iconic “tree skewered cenotaph” view (see at the text’s beginning), taken by Mr. Strobino in July 1989. All photographs courtesy Mr. Jean-Michel Strobino.

Rear view of the deteriorated cenotaph (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

Rear plaque with a perforation through the whole monument (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino )

Standing in front of the wrecked, albeit still solemn, monument, was a deeply emotional moment for the two friends; a prize for their arduous endeavor and the pride to rediscovering a great man’s memorial.

Mr. Strobino and his friend, Mr. Mongkhol Sasorith, in front of the monument (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

Apart from taking documentary pictures, there was nothing else to be done immediately. With some meager flowers, from the neighborhood, Mr. Strobino decorated the cenotaph and, after a last homage to Henri Mouhot’s memory, the pair returned to Luang Prabang.

A small flower decoration in homage to Henri Mouhot’s memory (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

Back in Vientiane, and before leaving Laos, Mr. Strobino shared his discovering with the French ambassador, and, in France, alerted the authorities of Montbéliard, Mouhot’s native city. His pictures documented the monument’s destruction and the urgency of a rehabilitation.

Answers, from all sides, where kindhearted; the French Embassy, in Vientiane, rapidly commanded the renovation work and, on 25th May 1990, the cenotaph was totally renovated and its neighborhood had been cleaned.

As a token to its courageous citizen, Montbéliard authorities had a marble plate engraved by a local craftsmen, Mr. Maurice Bloch. The 6,8 kg heavy piece was then shipped to Laos in order to be affixed to the cenotaph. Meanwhile, during another visit to Luang Prabang, in July 1990, Mr. Strobino organized a small inauguration ceremony for the renovated monument. He carried an official thankful missive from Montbéliard’s mayor, read it publicly at that occasion, and, later on, handed it over to the Lao minister of culture.

The plaque offered by the Montbéliard municipality, affixed in September 1990 (photographed 27 February 2013):

M. Jean-Michel Strobino during a visit to the restored monument (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

Mr. Strobino paying homage to Henri Mouhot’s memory with some flowers (Picture courtesy Mr. J.-M. Strobino)

5. Still an unsettled ending

This could be Henri Mouhot burial place’s saga denouement, the memorial’s happy end. After its rehabilitation, and the homage by the Montbéliard citizens, the year 1990, is also when Mr. Strobino concludes his account [2].

More then twenty years later, during my initial visit to the site, in 2012, I had mixed feelings. A dilapidated picnic place, greyish stones, faded engravings and untamed vegetation, produced an abandonment sense, not without charm, in the quiet jungle environment.

Some “decorative” elements, however felt odd. A French style road stone indicated “kilometer zero (lak soon)” and a concrete elephant was fossilized in a never-ending smile. I only understood later that these peculiarities resulted from a private initiative, without any symbolism or link to the explorer’s memory.

“Lak soon – kilometer zero” road stone freshly repainted, on Mouhot’s site (photographed 27 February 2013):

An ever-smiling concrete elephant statue (photographed 27 February 2013)

Another baffling item is a concrete effigy, often confused with Henri Mouhot itself, as in Lonely Planet guidebooks [11]:

« … His heavily bearded statue at the site looks altogether more cheerful … »

Actually, it represents August Pavie, whose bronze statues’ fate, in Laos, are another saga. This figure, however, is only a rough concrete copy.

Having Pavie watching over Mouhot’s memorial is not the worst discrepancy, but, as this is again a private initiative, there is no clear and harmonious integration. It is anyway inappropriate to deposit private and irrelevant elements on a shrine site.

Pavie’s concrete effigy, adorned with wasp nests, on Henri Mouhot’s site (photographed 14 October 2012)

Pavie’s concrete statue, cleaned (photographed 27 February 2013)

Non-sense graffiti on August Pavie’s statue (photographed 27 February 2013)

August Pavie’s concrete statue overlooking Henri Mouhot’s monument, another graffiti is written in its back (photographed 27 February 2013)

After the 1975 Pathet Lao forces arrival, Luang Prabang’s original Pavie bronze statue fall into disgrace, and was probably drown in the Mekong, or hidden somewhere. The embassy garden, in Vientiane, still hosts the other “original”, it is concealed, from general public sights, by the residence’s walls.

French embassy, Vientiane – August Pavie’s original bronze effigy by the French sculptor Paul Ducuing (photographed 25 May 2014)

The historic and commemorative value of Henri Mouhot’s burial place, on the the Nam Khan’s bank , resides in its solemnity, integrity and authenticity, which, in the same way that Luang Prabang’s heritage is protected by UNESCO, should be kept undisturbed for future generations. The Disneyesque concrete elements, deposited on the site, should be removed and put to better use, maybe along the picnic place.

In addition to maintenance and cleanings efforts, at Henri Mouhot’s memorial place, I noticed, during a December 2014 visit, a plasticized picture, adorned with a French flag ribbon. Here, again, I got a clue from Mr. Strobino, who was befriended with the depicted person: Pierre Mouhot, a fifth generation descendant of the explorer.

A plasticized Pierre Mouhot picture, a descendant of the explorer (photographed 3 December 2014)

Pierre Mouhot's picture and a small plaque at it's ancestor's burial place (picture courtesy J.-M. Strobino)

Pierre Mouhot was an active member of “Le Frangipanier” [8] a small humanitarian organisation operating in healthcare, education and cultural preservation. He passed away, in November 2013, at the early age of fifty-eight. Fulfilling his wishes, his widow had his ashes dispersed on his ancestor’s burial site. The ceremony was held on 5th August 2014, in the French ambassador’s presence and with local authorities.

Reminding August Pavie’s arrangement, with Ban Phanom’s inhabitant, to maintain the deceased explorer’s monument, His Excellency renewed the commitment, with Ban Noun Savath’s leader, to preserve the cenotaph; nowadays it is located on that village’s territory [10].

The rear monument’s plaque with the date corrected by the French Embassy (Photographed 27 February 2013)

6. Epilogue

Mr. Strobino’s additional information, about Henri Mouhot and its monument’s history, as well as readings about the Great Rivers’ exploration, have enhanced my sympathy and appreciation for that region. In itself, the Luang Prabang’s ring road completion, might not entice more visitors to the Nam Khan’s bank, informed travelers, however, will find it easier to call at the explorer’s burial place. As stated at my write-up’s beginning, there is nothing magnificent to the cenotaph itself; its beauty is in the site’s emotional value, a powerful means to recollect the past, a help to understand the present days.

Despite the progressing Laos modernization, the former jungle treks’ pavement to avoid Luang Prabang’s city center, the traditional Lue bamboo and wooden stilt houses replacement by concrete constructions, motorized vehicles instead of elephants and oxcarts, along with ubiquitous TV antennas, few things have really changed since the explorer’s times.

This is how Jules Roy describes the Nam Khan, as is flows, facing Henri Mouhot’s burial place (translate from the French text) [8]:

“On the opposite site, a dark boulders’ wall marks the torrent’s other rim: no dwelling, no human signs in the neighborhood. Only, from time to time, a light pirogue will cruise in front of this resting place, and the Laotian bargeman will glimpse with respect, maybe with fear, to this sad and touching memorial …”

The rocky Nam Khan in front of Henri Mouhot’s resting place (photographed 20 May 2014)

Traditional fishermen’s boats in Ban Phanom (photographed 24 February 2014)

A banyan tree, near Henri Mouhot’s monument

The classic and moody “Henri Mouhot’s last bivouac” engraving (published in “Le Tour du Monde” [14])

-----------------------

NOTES :

[1] Mr. Jean-Michel STROBINO is Nice city’s «Historic Heritage Center» Director. Historian and writer, he has intensively travelled off the beaten tracks, hiking, for instance, through a large part of the Himalayas. His interests also brought him to Indochina were he got enticed to research the exploration pioneer history. He wrote an Himalaya trekking guide and the first, French language, Vietnam guidebook.

In 1989, during a mission in Laos and by serendipity, he rediscovered Henri Mouhot’s monument, near Ban Phanom, and was instrumental its rehabilitation.

Mr. J.-M. Strobino’s publications listing:

Books:

Guide du Vietnam, Alticoop éditions, Nice, 1989

Vietnam, guida turistica, Calderini, Bologna, 1990 (en italien)

Himalaya, guide de trekking, Apsara éditions, 1992

Légendes du Laos, White Lotus Press, Bangkok, 2013 (traduction française)

Published papers :

Laos, le chemin de fer des canonnières, La Vie du Rail, n°2329, Janvier 1992

Histoire de la sépulture d’Henri Mouhot et de son monument funéraire 1861-1990, Bulletin de la Société d’Histoire Naturelle du Pays de Montbéliard, 2013, p.197-224

Peter Hauff, les aventures d’un marchand norvégien en Indochine au début du XXème siècle, Les Hors-Série de l’AICTPL, n°5, Juin 2013

Camoens, les Lusiades et le Mékong «portugais», Revue Philao, n°96, 3ème trimestre 2014, p. 22-27

André Escoffier, un autre poète (trop peu connu) du Laos, Revue Philao, n°98, 1er trimestre 2015, p. 23-27

Le commandant Diacre, un héros oublié du Mékong, Revue Philao, n°100

These papers can be downloaded in .pdf from the following link : ……………..

[2] The 150th anniversary of Henri Mouhot’s passing was commemorated, in 2011, in his native Montbéliard city. At that occasion, a French post stamp, with his effigy, was published.

J.-M. Strobino also contributed to the explorers’ remembrance with a particularly well documented and interesting write-up: “1861-1990, Histoire de la sépulture d’Henri Mouhot et de son monument funéraire”.

This document, in French but well illustrated, is available through the following link:

JM Strobino

Henri Mouhot’s commemorative post stamp

[3] This write-up is not about Henri Mouhot’s life, but mostly centered on his monument’s history. Information about the explorer’s life can be read in his travel account and in various online documents, for instance in Wikipedia:

Henri Mouhot - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

[4] Royal Society gold award - pdf listing (accessed and downloaded online): GoldMedallists18322011.pdf

In 1873, Stanley also got the “Patron's Medal - Henry Morton Stanley For his Relief of Livingstone, and for bringing his valuable journal and papers to England

[5] Mad About the Mekong: Exploration and Empire in South East Asia

John Keay

HarperCollins E-Books - Kindle Edition

[6] Travels on the Mekong, Cambodia, Laos and Yunnan

Louis de Carné

White Lotus, Bangkok, 1995

[7] Guy de Larigaudie was a French scout and traveler. In 1937/1938 he achieved the first link, by car, between Paris and Saigon, and, at that occasion passed Luang Prabang. Other than this, he is unrelated to Mouhot’s cenotaph or to the Mekong river exploration.

Guy de Larigaudie — Wikipédia

[8] Les Franc-Comtois en Orient – Henri Mouhot Premier Explorateur du Laos

Jules Roy

Dole Vernier-Arcelin, Editeur, 1884

Extract:

“Il fit part de ses projets d'abord à une société française qui ne lui offrit aucun secours, puis au gouvernement de l'Empereur qui lui refusa même le passage gratuit à bord de ses vaisseaux; mais les sociétés de géographie et de zoologie de Londres approuvèrent entièrement le plan de son expédition et l’aidèrent puissamment à l’exécuter”

….

“En face s'élève un mur de roches noirâtres qui forme l'autre rive du torrent : nulle habitation, nulle trace humaine aux alentours. Seule parfois une pirogue légère passera devant ce lieu de repos, et le batelier laotien regardera avec respect, peut-être avec effroi, ce souvenir triste et touchant du passage d'un homme de bien qui est tombé en précurseur de notre civilisation, en éclaireur de notre drapeau, à cinq mille lieues de sa patrie, à quatre cents du point le plus rapproché qu'habite un Européen!”

[9] Pierre Mouhot

Le Frangipanier - Éducation, formation professionnelle, culture et préservation du patrimoine

Villa Sisavad - Ban Sisavad Neua District Chanthabouly - Vientiane

[email protected]

[10] Pierre Mouhot’s ceremony in Luang Prabang with the French Ambassador (August 2014):

Déplacement de l’Ambassadeur à Luang Prabang

Le discours de l’Ambassadeur

La lettre de Pierre Mouhot adressée à son ancêtre Henri, lue par son épouse à cette occasion.

[11] Lonely Planet, Laos travel guides, 7th Edition, Dec 2010 and 8th Edition February 2014

Lonely Planet, however, is not the only publication to make the Pavie-Mouhot statue confusion, an uninformed visit undoubtedly leads to such a disorientation

[12] Captain Ernest Doudard de Lagrée

Ernest Doudart de Lagrée — Wikipédia

Histoire du monument dédié à Doudart de Lagrée

[13] Francis Garnier (second in command)

Francis Garnier, explorateur de l'Indochine et la confrontation Ferry, Clemenceau - Images du globe : histoire et sociologie politiques de ses représentations publiques

Monument à Francis Garnier — Wikipédia

GARNIER Francis (1839-1873) - Cimetières de France et d'ailleurs

Saint-Etienne-Hanoï-Paris: Francis Garnier

[14] Some public domain books about Laos and the Mekong exploration:

Henri Mouhot: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/46559/46559-h/46559-h.htm

Travels in the central parts of Indochina (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos, during the years 1858, 1859, and 1860, Henri Mouhot, Charles Mouhot, Murray publisher, 1864

In two volumes, Google books, public domain E-Book

Dr. Neiss book: Le Tour du monde : nouveau journal des voyages / publié sous la direction de M. Édouard Charton et illustré par nos plus célèbres artistes

Francis Garnier

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k58356827.r=Voyage+d'exploration+en+Indochine+Francis+Garnier.langFR

Travels in Indo-China and the Chinese Empire

Louis de Carné

Chapman and Hall, 1872

Free Google eBook

A signboard inviting travelers to visit Henri Mouhot’s monument on the Nam Khan’s bank.

A signboard inviting travelers to visit Henri Mouhot’s monument on the Nam Khan’s bank.

Attachments

-

02.jpg84.1 KB · Views: 573

02.jpg84.1 KB · Views: 573 -

_CH24051.jpg51 KB · Views: 526

_CH24051.jpg51 KB · Views: 526 -

NK7_0560.jpg65.9 KB · Views: 572

NK7_0560.jpg65.9 KB · Views: 572 -

NK7_4246-Modifier.jpg76.3 KB · Views: 544

NK7_4246-Modifier.jpg76.3 KB · Views: 544 -

_FJC6004.jpg84.1 KB · Views: 527

_FJC6004.jpg84.1 KB · Views: 527 -

NK7_2817.jpg77.5 KB · Views: 501

NK7_2817.jpg77.5 KB · Views: 501 -

NK7_0735.jpg84.1 KB · Views: 530

NK7_0735.jpg84.1 KB · Views: 530 -

NK7_0825.jpg71.1 KB · Views: 503

NK7_0825.jpg71.1 KB · Views: 503 -

NK7_2394.jpg84 KB · Views: 517

NK7_2394.jpg84 KB · Views: 517 -

P1070022.jpg113.6 KB · Views: 547

P1070022.jpg113.6 KB · Views: 547 -

NK7_4400.jpg83.2 KB · Views: 537

NK7_4400.jpg83.2 KB · Views: 537 -

NK7_4398.jpg61.6 KB · Views: 509

NK7_4398.jpg61.6 KB · Views: 509 -

NK7_4391.jpg91.5 KB · Views: 519

NK7_4391.jpg91.5 KB · Views: 519 -

NK7_2799.jpg70.1 KB · Views: 514

NK7_2799.jpg70.1 KB · Views: 514 -

NK7_2389.jpg40.6 KB · Views: 555

NK7_2389.jpg40.6 KB · Views: 555 -

NK7_4375.jpg84.8 KB · Views: 538

NK7_4375.jpg84.8 KB · Views: 538 -

NK7_2490.jpg84.2 KB · Views: 484

NK7_2490.jpg84.2 KB · Views: 484 -

NK7_2800.jpg63.2 KB · Views: 543

NK7_2800.jpg63.2 KB · Views: 543 -

NK7_2819-Modifier.jpg88 KB · Views: 516

NK7_2819-Modifier.jpg88 KB · Views: 516 -

NK7_2803-Modifier.jpg131.5 KB · Views: 529

NK7_2803-Modifier.jpg131.5 KB · Views: 529 -

NK7_0714.jpg98.9 KB · Views: 545

NK7_0714.jpg98.9 KB · Views: 545 -

NK7_0715.jpg64.1 KB · Views: 510

NK7_0715.jpg64.1 KB · Views: 510 -

NK7_2798.jpg107.7 KB · Views: 518

NK7_2798.jpg107.7 KB · Views: 518 -

NK7_2829.jpg93.8 KB · Views: 549

NK7_2829.jpg93.8 KB · Views: 549 -

_FJC5814.jpg76.3 KB · Views: 527

_FJC5814.jpg76.3 KB · Views: 527 -

_JC12845.jpg98.8 KB · Views: 520

_JC12845.jpg98.8 KB · Views: 520 -

8.jpg61 KB · Views: 524

8.jpg61 KB · Views: 524 -

01.jpg91.7 KB · Views: 513

01.jpg91.7 KB · Views: 513 -

boue.jpg111.1 KB · Views: 578

boue.jpg111.1 KB · Views: 578 -

NK7_0762.jpg27 KB · Views: 546

NK7_0762.jpg27 KB · Views: 546 -

Mouhot%252520monument%252520%252520Lanoye.jpg69.1 KB · Views: 395

Mouhot%252520monument%252520%252520Lanoye.jpg69.1 KB · Views: 395 -

_FJC6003.jpg83.8 KB · Views: 525

_FJC6003.jpg83.8 KB · Views: 525 -

_JC18309.jpg69.4 KB · Views: 525

_JC18309.jpg69.4 KB · Views: 525 -

_JC18337.jpg95.5 KB · Views: 496

_JC18337.jpg95.5 KB · Views: 496 -

NK7_0727.jpg107.3 KB · Views: 510

NK7_0727.jpg107.3 KB · Views: 510 -

_FJC6002.jpg105.4 KB · Views: 525

_FJC6002.jpg105.4 KB · Views: 525 -

NK7_0753-Modifier.jpg113.3 KB · Views: 513

NK7_0753-Modifier.jpg113.3 KB · Views: 513 -

NK7_2809-Modifier.jpg100.2 KB · Views: 510

NK7_2809-Modifier.jpg100.2 KB · Views: 510 -

NK7_0742-Modifier.jpg75.7 KB · Views: 508

NK7_0742-Modifier.jpg75.7 KB · Views: 508 -

NK7_0743.jpg64.7 KB · Views: 514

NK7_0743.jpg64.7 KB · Views: 514 -

NK7_0737-Modifier.jpg107.6 KB · Views: 533

NK7_0737-Modifier.jpg107.6 KB · Views: 533 -

P1290153.jpg74.4 KB · Views: 493

P1290153.jpg74.4 KB · Views: 493 -

P1050273%25255B1%25255D.jpg66.2 KB · Views: 504

P1050273%25255B1%25255D.jpg66.2 KB · Views: 504 -

NK7_0761.jpg49.3 KB · Views: 501

NK7_0761.jpg49.3 KB · Views: 501 -

JMS-fleurs.jpg81.8 KB · Views: 530

JMS-fleurs.jpg81.8 KB · Views: 530 -

JMS%2525202.jpg100.4 KB · Views: 527

JMS%2525202.jpg100.4 KB · Views: 527 -

_CH13595.jpg77.9 KB · Views: 500

_CH13595.jpg77.9 KB · Views: 500 -

_FJC6096.jpg54.5 KB · Views: 483

_FJC6096.jpg54.5 KB · Views: 483 -

NK7_2828.jpg109.4 KB · Views: 495

NK7_2828.jpg109.4 KB · Views: 495 -

102.Bivouac%252520en%252520for%2525C3%2525AAt.jpg128.3 KB · Views: 394

102.Bivouac%252520en%252520for%2525C3%2525AAt.jpg128.3 KB · Views: 394 -

_JC12839.jpg61.6 KB · Views: 498

_JC12839.jpg61.6 KB · Views: 498 -

NK7_0724.jpg39.8 KB · Views: 476

NK7_0724.jpg39.8 KB · Views: 476 -

P1050284.jpg56.5 KB · Views: 495

P1050284.jpg56.5 KB · Views: 495 -

_FJC6034.jpg70.8 KB · Views: 502

_FJC6034.jpg70.8 KB · Views: 502 -

_FJC7064-2.jpg86.8 KB · Views: 467

_FJC7064-2.jpg86.8 KB · Views: 467 -

NK7_0749.jpg130.2 KB · Views: 509

NK7_0749.jpg130.2 KB · Views: 509 -

104%252520timbre.jpg105.3 KB · Views: 478

104%252520timbre.jpg105.3 KB · Views: 478 -

NK7_2490.jpg84.2 KB · Views: 496

NK7_2490.jpg84.2 KB · Views: 496

Last edited by a moderator: